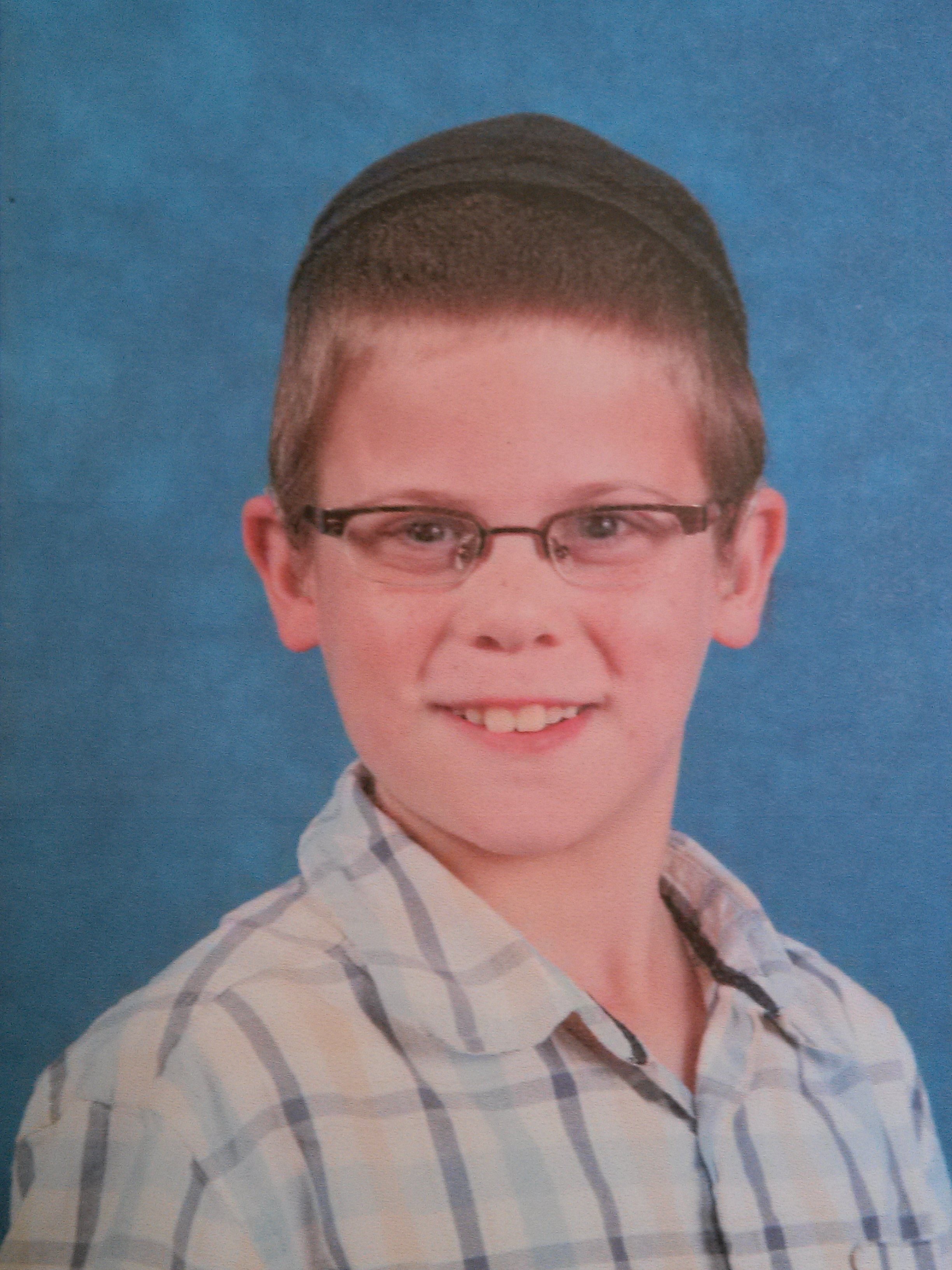

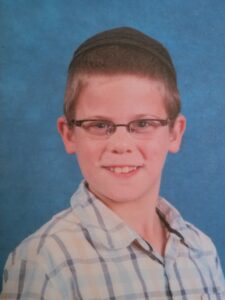

Six years ago, when Eli, my bechor, was in fourth grade, I met his rebbi and asked him how my son was doing. I was expecting to hear the usual:

Six years ago, when Eli, my bechor, was in fourth grade, I met his rebbi and asked him how my son was doing. I was expecting to hear the usual:

Eli’s a good boy, he’s learning well, he has lots of friends.

Instead, to my dismay, the rebbi said, “I think Eli is losing his geshmak for learning. He’s not enjoying the learning as much as he did at the beginning of the year.”

What am I supposed to do now? I thought to myself. I’m not a mechanech!

But then another thought occurred to me: If the Torah commands us, “V’shinantam l’vanecha,” it must be that every father has the ability to teach his son Torah.

From then on, I started to sit with Eli every night and review what he had learned that day in Lakewood’s Yeshiva Toras Aron. It took some trial and error, but after a while I figured out how to make our joint learning pleasant for him, which was my primary goal. In fact, Eli began to enjoy our learning so much that he would actually rub his stomach in delight while we learned, as though he had just eaten a delicious meal.

On Motzaei Shabbos, I would learn with Eli at the AvosUbanim program in the Alumni Bais Medrash of Lakewood’s Beth Medrash Govoha (BMG). At times, Eli would ask me a question, and if he was not satisfied with the answer I gave, he would turn to the yungeleit learning nearby and pose his question to them. He barely knew these people, but he looked up to them as his heroes and felt comfortable approaching them.

Whenever we would host bochurim for Shabbos meals, Eli would go over to them and ask, “So what are you learning now?” When the surprised bochurim would name the masechta they were learning, Eli would pepper them with questions and get them to explain what the masechta was all about.

Another interesting thing Eli did was that he took upon himself the task of covering and uncovering the seferTorah on Shabbos between each aliyah in BMG’s 11th Street beis medrash, where we davened. When I asked him why he wanted to do this, his response was, “What, I should just let the sefer Torah sit there open?”

On Friday, 12 Adar II 5774, about five months after I started learning with Eli every day, I learned with my chavrusa before davening and then headed to a bris that my friend was making. I had just put on my tefillin and was hanging up my coat when my chavrusa hurried over to me, his face furrowed in concern, and handed me his phone.

“Your wife is on the line,” he said. “It doesn’t sound good.”

It was actually worse than I could have imagined.

“Eli didn’t wake up this morning,” my wife said urgently. “Hatzolah is here trying to revive him.”

Boom!

“There’s a fellow from Hatzolah outside waiting to drive you home,” my chavrusa said.

Dumbly, I handed my own car keys over to him and entered the Hatzolah car.

I walked into my house to find my dining room filled with Hatzolah members, who were trying to pump life into Eli’s still body.

“This isn’t working,” they told me gravely. “We need to take him to the hospital.”

In the hospital, Eli’s death, due to unknown causes, was confirmed. I remember feeling deeply hurt when police officers sat down with my wife and me separately “just to ask a few questions” and rule out foul play. As though this nightmare weren’t bad enough, we had to defend our parenting and convince them that we weren’t responsible for our son’s sudden, inexplicable death in his sleep.

While still in the hospital, I was surrounded by relatives and friends who all seemed to be bawling their heads off, while I, curiously, wasn’t crying or feeling any strong emotion. I remember calling my rebbi and asking him, “Do you have a chair near you?”

“What’s going on?” he asked.

When I told him, his voice dropped to a whisper.

“I have to get off the phone,” he rasped.

I wasn’t sure what type of reaction I had expected, but having him hang up on me was certainly not it. Later, I would find out the reason why he had hung up so abruptly: Upon hearing the news, he had felt that he was going to faint, and after he hung up the phone he actually did pass out.

I didn’t feel faint, though. And while my wife was crying together with our other family members, I was strangely composed.

A relative of mine was present when I called my morning seder chavrusa and calmly told him, “I don’t think I’m going to be there today.”

My relative looked at me as if I was off the wall.

We chose to hold Eli’s levayah outside BMG’s main building, because Eli had so greatly admired the yungeleitand bochurim of the yeshivah. When I asked my rebbi to speak at the levayah, he demurred, saying it was too hard for him. It was then that he explained to me why he had hung up the phone earlier that day, and I felt tremendously comforted to hear that my rebbi felt my pain even more powerfully than I did.

At the Shabbos seudah that night, my five-year-old son turned to me and said, “Tatty, my salad is crying.”

I felt a stab of pain, but I steeled myself to maintain a confident façade. There’s an Eibeshter in the world, I told myself. Everything He does is somehow good for us, and He’s with us in our pain.

“Oh, your salad is crying?” I said. “That’s very interesting. I’m not going to cry today, because it’s Shabbos, but your salad can cry gezunterheit.”

A minute later my son turned to me again and said, “Tatty, my heart is crying.”

Another stab of pain. “Oh, your heart is crying?” I replied. “Wow, that must be really hard. I’m not going to cry today, because it’s Shabbos, but your heart can keep on crying.”

I realized, already then, that I had two choices: I could crumple together with my son, or I could hold strong and be a pillar of support for him, and for the rest of the family.

I chose to do the latter. The Eibeshter wants us to move forward, I thought, and He’s going to help us do that.

While my reaction to the tragedy differed from that of most of my relatives — I did not express my pain outwardly by crying — the void inside me was so intense that I felt as though it was going to suck me in. I remember remarking to people, during the shivah, that I had never known that the heart is capable of plunging so deeply. In order to cope with the overwhelming grief, I had to keep telling myself, I’m okay right this second. Yes, I feel a tremendous sense of loss, but I’m not going anywhere, and I can live with this feeling for the next ten minutes and survive.

That thought carried me through the shivah and beyond. Ten minutes became 20, then 30, then an hour, then an entire day.

When shivah ended and I had to return to regular life, I often felt that the world was crumbling around me, and at those times I would tell myself, Is the world really crumbling? No. Everything is the same as before, except that now there’s this gaping void and this overwhelming pain. I can’t do anything about that right now and I don’t have to do anything about it — I don’t have to beat it down, and I don’t have to hide it. I just have to carry on with my life, with the pain, and make the best of it.

People urged me to talk to people and seek chizuk in order to process my grief, and in the beginning I did speak to some rebbeim, but although they said beautiful, uplifting things, their words didn’t resonate with me. Focusing on the loss left me feeling sad and depressed; I wanted to do something with the pain, to turn it into something constructive.

But what could I do?

I pondered the various things that had been said about Eli during the shivah.

Many people had marveled at how nine-year-old Eli had showed such strong leanings toward ruchniyus. One bochur who came to be menachem avel told us that he had once gotten a ride in a car together with Eli, who promptly turned to him and asked, “Can you tell me a vorton the parshah?”

“Sorry,” the bochur responded, “I don’t have a vort.”

“That’s okay,” Eli said. “So I’ll tell you a vort.” And he did.

A number of fathers told me that when they came to AvosUbanim, their sons were entranced by the sight of Eli and me learning together. “There was a certain excitement in how your son learned,” they observed. “He loved learning.”

Eli didn’t only love Torah — he loved people, too. Even at his young age, he knew how to make others feel good. After eating a meal in his aunt’s house, he turned to her and declared, “Tante Bracha, the food was absolutely delicious!”

At the levayah, my father-in-law related that Eli had recently come to him and said, with youthful purity, “Zeidy, can you give me a brachah? And then I’ll give you a brachah, too.”

My daughter, who was a year younger than Eli, asked worriedly, “If Eli’s not here, then who’s going to make sure the whole family is b’shalom?”

Shortly after shivah, I asked the organizers of AvosUbanim if I could address the attendees for a couple of minutes. At first, they were hesitant, fearing that I would overwhelm the kids with tears and emotion, but I assured them that I was not planning to do that. Instead, I stood up before a crowd of 2,000 kids at the Avos Ubanim awards ceremony and showed the boys Eli’s Avos Ubanim card, which had holes punched for almost every week that year until his petirah. “Please learn just one mishnah l’illuinishmaso,” I asked of the boys. “If you learn it well and really understand it, it will be a tremendous zechus for him.”

That wasn’t enough, though. I still felt a tremendous need to translate my pain into something positive. One day, I turned to one of my friends, who is a well-connected, capable person, and said, “We have to do something in Eli’s memory. What’s the reid around town? What do people need?”

My friend informed me that there had been talk of yungeleit forming an organization to help other yungeleitmake Yom Tov.

“Most of the year, these families make it through the month,” he explained, “but they can’t cope with the Yom Tov crunch.”

This idea appealed to me, because I myself know what it means to live on a kollel budget. Between my wife’s earnings and the small stipend I receive from yeshivah, plus money for shemiras hasedorim, we manage to pay our bills, but the prospect of making Yom Tov is daunting.

I could hardly envision myself as a fundraiser, though. Several years earlier, a few of my relatives had banded together to raise money for a certain cause, and they tried to persuade me to join them in the effort. I wiggled my way out of it, not knowing what to do with myself when sitting before a gvir and having no idea what to say when I was supposed to be asking people for money.

“I don’t know how other people fundraise,” I had told my wife at that time, “but it’s definitely not for me.”

I thought of how nine-year-old Eli had eagerly approached the yungeleit in the Alumni Beis Medrashwith his questions. I thought of how he had so naturally turned to a total stranger in the car and asked him to share a vort on the parshah. I thought of how he had stepped up to cover the sefer Torah because no one else was doing it.

And I knew this was something I had to do.

That very day, I wrote a deeply emotional letter to the community requesting that people translate their shock and grief upon Eli’s petirah into something constructive by donating to a new organization called Kupas Yom Tov, with the goal of helping kollel families in Lakewood meet their Yom Tov expenses.

By Rosh Chodesh Nissan, just two weeks after Eli’s petirah, posters had gone up all over the various bateimedrash of BMG with a picture of Eli Raitzik and a request for donations to the nascent Kupas Yom Tov. In the span of a week, we raised $90,000, a sum we considered remarkable.

Even more remarkable were the letters that poured in to Kupas Yom Tov. Along with their donations, people sent personal letters to me expressing their sympathy for our loss. One of these letters, from a rosh chaburah in BMG whom I barely knew at the time, was so meaningful that I placed it in my wallet, where it has remained until this day. In the letter, the rosh chaburah expressed his admiration of what Kupas Yom Tov was doing and described what a great zechus it is for my family and for Eli.

Reading these letters, I realized that I had actually done the community — and myself — a favor by giving people a forum through which to reach out to me without causing discomfort to anyone. When a person goes through a tragedy, Rachmana litzlan, people typically walk on eggshells around them, not wanting to ignore the person’s pain but also not wanting to bring up the loss for fear of triggering additional grief. People are unsure whether to say something, what to say, and when to say it. They want to help, but they don’t know how, and they’re often afraid to ask what they can do.

Through Kupas Yom Tov, people had a natural way of showing that they cared, that they felt our pain, that they wanted to help. And for me, this heartwarming response to my appeal for donations was the greatest nechamahpossible. I didn’t want to wallow in tears and grief or talk out my pain with anyone. I just wanted to do something meaningful for Eli — and I knew this was something that would have made him happy.

Back then, Kupas Yom Tov was a small-time organization run by a handful of yungeleit, including myself, and no one dreamed that it would turn into a large-scale operation. Since that first campaign, however, Kupas Yom Tov has grown and grown, to the point that we now disburse close to $2 million a year and help over a thousand families in Lakewood enjoy Yom Tov.

I can’t say that I ever overcame my innate aversion to fundraising, but the primal need to channel my pain into doing something for Eli still propels me to do whatever is necessary to promote Kupas Yom Tov, no matter how uncomfortable or awkward I feel. Whether it’s making announcements in yeshivah that people should give to Kupas Yom Tov, approaching unfamiliar gvirim to solicit donations, or speaking at parlor meetings about my personal tragedy and how it spurred me to start this organization, I’m always ready to put my personal discomfort aside for the sake of this cause.

When I approach a wealthy person for a donation and he responds with ambivalence — “I have to think about it, let me get back to you” — I don’t back off. Instead, I feel compelled to put in another word for the organization and continue talking until I convince him of the importance of what we are doing.

Once, in the early days of Kupas Yom Tov, someone in Lakewood called up to express his indignation over the founding of the organization. “Who gave you the right to go and open a tzedakah organization?” he demanded.

I didn’t exactly understand his issue, but I started telling him how and why Kupas Yom Tov was started. When he realized that he wasn’t just talking to a macher who had randomly started a tzedakah organization, but rather to a bereaved father who had channeled his pain into a worthwhile cause, he got off the phone really fast.

To this day, people associate Kupas Yom Tov with Eli and tell me that the success of the organization must be in his merit. Hearing this is a tremendous chizuk to my family and me, and that drives us to continue devoting ourselves to the organization.

Each year before Succos and Pesach, I write a personal letter to the community. The focal point of my letters, and of Kupas Yom Tov in general, is the idea that Yom Tov is not just about rejoicing with the Ribbono shel Olam — it’s also about bringing joy to others, and especially to those who hold up the world through their Torah learning.

In the early years after Eli’s petirah, I was careful to grab the return envelopes for Kupas Yom Tov out of my mailbox as quickly as possible, for fear that their presence would cause pain to my wife and children. I also made sure that the time I devoted to the organization would not come at their expense, as I didn’t want my personal nechamah to cause them pain. I therefore scheduled most of my meetings for late in the evening, when I wasn’t needed at home, or during bein hazmanim, when my learning schedule was lighter. Since Kupas Yom Tov’sbusy times are Tishrei and Nissan, which are mostly beinhazmanim anyway, my involvement with the organization fit quite naturally into my schedule.

As time went on, however, and the pain of Eli’s loss dulled somewhat, my family started to connect with the Kupas Yom Tov concept and actually get excited when we launched our biannual campaign. When the mailbox filled with envelopes bearing donations, my children would gleefully bring me the mail, delighted that people were giving to Eli’s tzedakah.

By now, Kupas Yom Tov boasts a cadre of dedicated individuals, mostly volunteers, who have taken over much of the technical work of running the organization, so I no longer have to be as busy with that end of its operations.

One task I reserve for myself, though — not that anyone else is volunteering — and that is making phone calls to donors on the afternoons of Erev Succos and Erev Pesach to ask them to cover Kupas Yom Tov’s last-minute shortfall. After helping with my family’s Yom Tov preparations, I devote the afternoon hours to raising the last bit necessary to help other families.

It’s my way of making sure that Eli continues to be part of our own Yom Tov.

To donate to Kupas Yom Tov click here HERE or go to Kupasyomtov.org or call 732-330-5914