James Bellis is already in a bind. As an employer, he pays higher state unemployment taxes than many because he lays off about a dozen seasonal workers from his tree maintenance business every winter. But next year, he expects to be forced into a deeper hole. Businesses will likely see their unemployment taxes skyrocket in July — and not come down for years — because the fund is broke. It’s almost more than Bellis can handle, after seeing a 23 percent drop this year at Tree Tech, his Randolph business.

James Bellis is already in a bind. As an employer, he pays higher state unemployment taxes than many because he lays off about a dozen seasonal workers from his tree maintenance business every winter. But next year, he expects to be forced into a deeper hole. Businesses will likely see their unemployment taxes skyrocket in July — and not come down for years — because the fund is broke. It’s almost more than Bellis can handle, after seeing a 23 percent drop this year at Tree Tech, his Randolph business.

“In this economy, every dollar is valuable to managing a business,” he said.

State and national labor experts echo Bellis, saying the higher taxes could work against efforts toward economic recovery by stifling hiring and wages.

Gov.-elect Chris Christie’s administration says the unemployment fund is one of the top three financial problems it will face when it takes over on Jan. 19.

“It’s a very serious problem, and, frankly, it’s as serious of any of the state’s fiscal problems,” said Rich Bagger, Christie’s chief of staff.

The fund has been strained by a persistent unemployment rate of close to 10 percent, but legislators and national observers say the problems stem from years of pillaging by lawmakers during better times to pay for other projects.

Because the fund is insolvent, employers will see an automatic tax hike in July, which could translate into businesses paying between $300 and $1,100 more per worker to bring $1 billion more to the state, according to the state Labor Department.

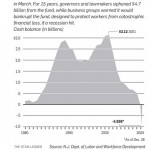

But even that will not stop the fund’s deficit from increasing fivefold, from $926 million now to $4.5 billion by the end of April 2011. New Jersey is one of 25 states that has borrowed money, interest-free through 2010, from the federal government.

The situation is doubly unpleasant for Christie, who has promised no tax increases, because the hike is baked into the unemployment system. It automatically adjusts the tax rate based on the fund’s balance and an employer’s individual history of layoffs.

The tax hike could work against an economic recovery, causing businesses to hire fewer people, lay off workers or freeze or lower salaries, said Rich Hobbie, executive director of the National Association of State Workforce Agencies.

“This is a serious increase in costs for employers,” he said. “They have to figure out some way to cover that cost.”

The tax increase comes at the worst time for businesses, said Art Maurice with the New Jersey Business and Industry Association.

“Employers are struggling to keep people working that they have on their payrolls now,” he said. “Now to add an across-the-board (unemployment insurance) payroll tax increase on top of that would just be backbreaking.”

Bagger said the administration must look at all possible options to revive the once-flush fund that now supports more than 175,000 New Jersey residents. The choices include:

• Pushing legislation to put off or reduce the tax increase. The downside is that increases debt.

• Reducing benefits to bring them more “in line” with other states. Democrats and worker advocates will fight that change.

• Finding $1.9 billion for the fund. But from where? Gov. Jon Corzine just cut $839 million in spending to deal with a nearly $1 billion current budget deficit, and the Christie team projects it will be $9.5 billion short for next year’s budget.

• Teaming with other states to ask the federal government to forgive loans.

Lawmakers have known this was coming for years. Over the last two years, Corzine pushed off similar tax increases on employers by putting $380 million from the general fund into the unemployment fund.

The U.S. Department of Labor expects 40 states’ funds to become insolvent by 2011.

Already, 25 states and the Virgin Islands have borrowed more than $25 billion from the federal government to pay claims, not including extended benefits paid for by the federal government. New Jersey started borrowing in March and now owes more than $926 million. The biggest borrower, California, owes $5.9 billion. Michigan owes $3 billion and New York owes $2 billion. The states’ problems are not unprecedented. In the 1970s and ‘80s, states borrowed regularly from the federal government, but loans at that time were interest-free. This time around, loans are interest-free only though 2010

State lawmakers around the country are scrambling to deal with the problem.

New Hampshire, for example, has instituted a one-week waiting period to get benefits and increased the portion of salary taxed. Indiana in April saw thousands of union workers protesting cuts the governor there called “Rolls-Royce” benefits. And 10 states are already making employers pay their system’s highest tax rate, which is what New Jersey is scheduled to do.

New Jersey legislators disagree about how to solve the problem.

New Jersey has one of the highest weekly benefits — $584, compared with $405 in New York and $566 in Pennsylvania — and it will automatically increase to $600 for newly laid off workers who receive their first benefit check after the New Year.

It also is one of a handful of states to allow people to collect checks the first week they are unemployed — instead of waiting a week — and which allows increased benefits for people with children, according to the National Association of State Workforce Agencies. Advocates say this is because it costs so much to live here.

Still, some legislators say the state can’t afford to categorically leave out options.

“Everything should be on the table,” said Assemblyman Joseph Malone (R-Burlington), who said the solution to the fund’s problem needed to be worked out with a comprehensive approach to fixing the economy. “The decisions that are going to have to be made are going to anger people.”

The very suggestion has drawn sharp words from some legislators and advocates.

“Given the dire situation it’s just mean-spirited,” said state Sen. Barbara Buono (D-Middlesex.) “I think that it would be unconscionable, given the current state of affairs, to decrease benefits. We’re talking about people keeping a roof over their heads and keeping food on the table.”

An alternative approach, offered by state Sen. Stephen Sweeney (D-Gloucester), is to let the pot just replenish itself.

“These funds have to build up, and they can’t build up overnight,” he said.

To be sure, even the more generous features are not what caused the fund to fail. The major source of the problem, critics say, is not even the recession, but rather the $4.7 billion siphoned from the 1990s through 2006 by governors and legislators from both parties to pay for things such as health care for the poor.

“Unemployment wasn’t so long-term back then,” said Buono, who supported the diversions. “Given the set of alternatives that we had and the cuts that were made, this was not anything that any individual legislators wanted to do but … I think it was something that needed to be done at the time.”

The unemployment fund kept growing, reaching $3.1 billion by the end of 2001. But even after the balance slipped, plunging to $1.5 billion by the end of 2003, governors and legislators continued to scoop up money before it hit the fund, until Corzine stopped the practice in 2006.

The state has started to take steps to prevent that from happening again. In November, voters will decide on a constitutional amendment that would prevent the Legislature from diverting money.

As an employer, Stephen Fauer said he accepts helping others. But what bothers Fauer, who owns Environmental Strategies and Applications in Middlesex Borough, is the reason he will likely have to pay more.

“It’s the irresponsibility of our politicians,” he said. “Doing things for expediency rather than things that are correct. You need to behave in a way that’s correct. You need to behave in a way that’s responsible.”

How it works

Employers and employees both contribute to the fund. But employees put in a small, fixed amount, whereas employers pay the lion’s share of the tax – and the amount they pay varies.

The system taxes employers based partially on how much money is in the fund, and partially based on their history of laying off workers.

But there’s another factor: All employers are affected by how much money is in the unemployment pot. If the balance sinks too low, taxes go up for everybody, which is happening this year. Star Ledger.